When the roots of modern-day polyamory, sexual freedom, and “free love” are discussed, they’re often traced back to the 1960s—the era of hippies, the movement for queer rights, and the “sexual revolution.” But in the U.S., those ideas are a century older still: The above video looks back at the life and legacy of Victoria Woodhull who, in the 1870s, was advocating for people to have the rights to love who they loved—without interference from the government.

“She was probably the most famous woman in America at the time,” says Michael Bronski, author of A Queer History of the United States and Professor of the Practice in Media and Activism at Harvard University.

[time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

Woodhull was a stock broker and newspaper publisher best known for being the first woman to testify before a U.S. House committee in 1871—in favor of women’s suffrage—and as the newly formed Equal Rights Party’s first candidate for President in 1872. (Woodhull lost to Ulysses S. Grant, but her Party’s ideas have, in many senses, lived on.) Woodhull and activists formed the Equal Rights Party as a kind of “People’s Party” to challenge the fact that women couldn’t vote, and to raise awareness social issues from labor union rights to temperance, according to Lisa Tetrault’s The Myth of Seneca Falls: Memory and the Women’s Suffrage Movement, 1848-1898.

Woodhull’s platform was also inspired by aspects of the “Free Love” movement, a grassroots movement that believed “the state had no right to dictate how people led their personal lives around romance and sexuality,” according to Bronski. Utopian socialist and philosopher John Humphrey Noyes has been credited with coming up with the term “free love” in 1848 and for starting a swingers communities in upstate New York, one of several communal living experiments that cropped up nationwide in the mid-1800s as a reaction to the industrial revolution’s emphasis on capitalism.

Woodhull learned about the movement from Stephen Pearl Andrews, a writer for Woodhull’s newspaper Woodhull and Claflin’s Weekly. She was heterosexual, but the movement’s ideals appealed to her as someone who had been divorced—Woodhull would marry three times in her lifetime. This was considered scandalous at the time for a woman, let alone one in the public eye.

“She was married by the time she was a teenager to a man who was significantly older than her. It was not a good marriage by any means,” says Teri Finneman, associate professor in the School of Journalism and Mass Communications at the University of Kansas and author of the book Press Portrayals of Women Politicians, 1870s-2000s. “She felt it was really unfair that men could go around and have affairs. It was considered just part of society, while women had no other choices.”

Woodhull explained what “Free Love” meant to her in her most famous speech, “And the Truth Shall Make You Free: A Speech on the Principles of Social Freedom,” on Nov. 20, 1871, to a crowd of 3,000 people at Steinway Hall in New York City:

Yes, I am a free lover. I have an inalienable, constitutional and natural right to love whom I may, to love as long or as short a period as I can; to change that love every day if I please, and with that right neither you nor any law you can frame have any right to interfere. And I have the further right to demand a free and unrestricted exercise of that right, and it is your duty not only to accord it, but as a community, to see I am protected in it. I trust that I am fully understood, for I mean just that, and nothing else.

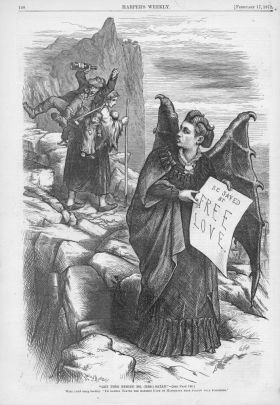

Such a position was controversial. An 1872 Thomas Nast cartoon dubbed Woodhull “Mrs. Satan,” parodying the pushback from conservatives. “The press wrote that her ideas were preposterous and revoltingly, indecent and nasty, and so she got a very strong lashing for having these kinds of liberal, open views as far as marriage and sexuality,” says Finneman.

Woodhull died in 1927 at the age of 88. And while the “Free Love” movement doesn’t boast concrete policy accomplishments, it did succeed in starting a conversation. “It was enormously effective in terms of getting people to think, and talk about, these issues,” Bronski explains. “They set the stage for a new way to think about idea of personal freedom and what people were allowed to do in their personal lives.”

Scholars say Woodhull’s 1870s vision of personal freedom is universal can be applied more broad to a range of issues. “I have students ask me, ‘Did [Woodhull] advocate for gay rights back then?'” says Finneman. “The general theme of what she was saying is still very applicable today, as far as…’who is anybody else to judge my love life and who I want to spend time with?'”

0 Comments