There are sounds that humans make with intention. Then there are the wordless sounds we make when our emotions take over—the sounds that, in their texture and tone, speak even more clearly.

Guilty, Hennepin County Judge Peter Cahill said, as he read the jury’s April 20 verdict on the first of three charges leveled against former Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin in the murder of George Perry Floyd Jr. That’s when I heard those involuntary sounds come up and out.

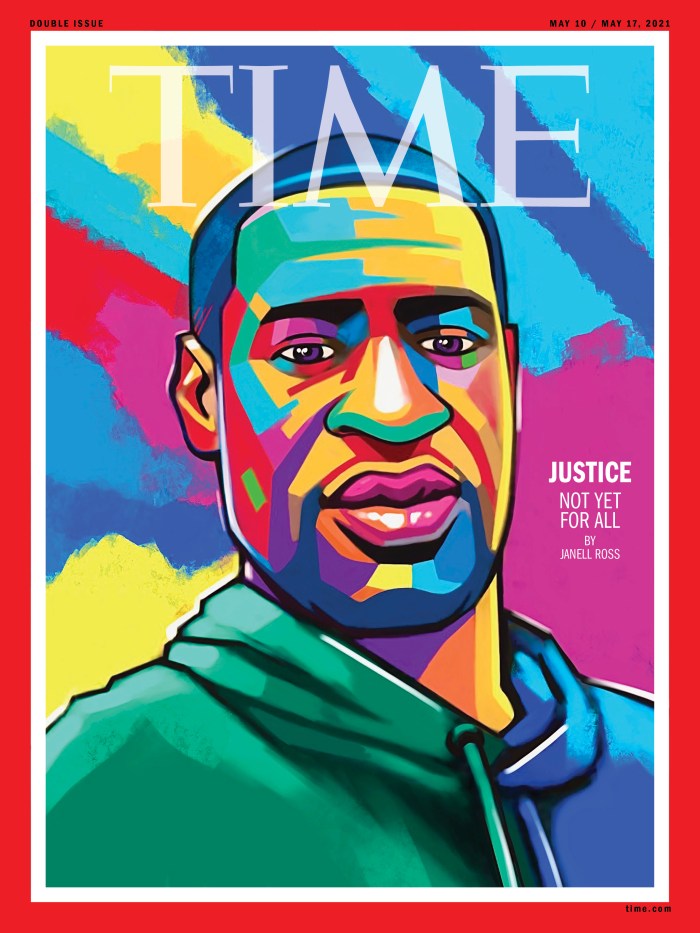

Get a print of TIME’s George Floyd “Justice—Not Yet For All” Cover

It was the collective sound of shock, filtered through deep pain, followed by relief. It filled a third-floor Hilton Hotel ballroom, where Floyd’s family watched the local NBC station on a movie theater-sized screen. Many had come from distant places for this moment—Houston, Charlotte, N.C., New York City. They’d carefully slipped away from the direct stares of the overwhelmingly white press that had begun to tail and track them. (Photojournalist Ruddy Roye and I, as well as a documentary team, were the only members of the media present in the room.) They had gathered in that ballroom, with its collapsible walls and busily patterned carpet, because COVID-19 and security restrictions kept them from the courtroom. And because they had reason to want the moment kept semi-private. Because they loved George Floyd, they had faith Chauvin would be held accountable—but they all knew that, statistically speaking, the trial was not likely to end the way it did.

As two additional guilty verdicts followed, the volume rose. The screams became more confident, more affirmational and appreciative of what a jury of 12 Americans had done. They had, for the first time in Minnesota history, convicted a white police officer of murdering a Black man while on duty. Chauvin, who during a May 25, 2020, arrest had held Floyd down with his knee for more than nine minutes even as Floyd declared that he could not breathe, would now face up to 40 years in prison.

Brandon Williams, George Floyd’s nephew whom Floyd considered a son, leapt into the air. Then, someone, a man on the far side of the ballroom, cried out—this time with intention, with words that had become familiar in the more than 10 months since Floyd’s murder: “Say his name!”

“George! Floyd!”

“Say his name!”

“George! Floyd!”

“Who made America better?”

“George! Floyd!”

People do not react with uncontrollable cries nor with the sounds of street protest when they have confidence that the constitution’s guarantee of universal equality will be as reliably extended to them as it is to those who are police officers. This is the way people react when history—distant and recent—obliges them to warn their children about the dangers of law enforcement and common criminals alike. Ours has always been a country of both law and—where Black Americans are concerned—lies.

From the very beginning of this country, when Thomas Jefferson wrote the Declaration of Independence, with such moral authority and clarity that most Americans today can still recite its claims about the inalienable rights of man, he did so aided by the wealth and privilege he derived from exploiting and enslaving human beings.

Read more: The Story Behind TIME’s George Floyd ‘Justice—Not Yet For All’ Cover

In the 1840s, a Virginia-born slave named Dred Scott tried to turn to the law for justice. He sued his enslaver for emancipation on the grounds that he’d been made to work in a free territory that is today part of Minnesota. Roger Taney, Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, issued a ruling that declared Black people could not be citizens and “had no rights which the white man was bound to respect.” The decision was among the things that put the country on a collision course for the Civil War.

And just 30 years ago, a group of white officers in Los Angeles were caught on video tape, beating, kicking and punching a lone Black man named Rodney King. A suburban Simi Valley jury did not convict any of the four officers of use of excessive force or assault.

On the morning of the Chauvin verdict, “fate and irony” brought America’s attention back to Minnesota, Benjamin Crump, a lawyer representing the Floyd family, told me. This is the land where Dred Scott had no rights. Just three decades ago it would have been unthinkable to get a criminal indictment, much less a conviction, against a white officer who killed a Black person, Crump said.

Chauvin’s lawyer Eric Nelson had tried but failed to place a litany of conflicting, complicating and sometimes cynically racist suggestions about Floyd’s cause of death in the jury members’ minds—placing the blame on the person to whom the terrible thing happened, a brand of gaslighting familiar to every Black person in America who has attended school, worked, attempted to become a homeowner, sought health care or had any contact with the criminal justice system. Chauvin’s team wanted the jury to believe that the eyewitnesses to Floyd’s murder were an angry and mostly Black mob who distracted Chauvin. That Floyd was large and strong enough to resist two other officers, but in ill enough health that an enlarged heart or a substance addiction or exposure to carbon monoxide from a nearby tailpipe could have really caused his death. But the prosecution was able to counter those arguments with facts. Floyd was in the main kind, strong and healthy. What had stopped his heart was Chauvin’s knee and Floyd’s position, handcuffed face down on the street. By Tuesday afternoon the world had seen Chauvin leave the courtroom in handcuffs.

Read more: The Intersection Where George Floyd Died Has Become a Strange, Sacred Place. Will Its Legacy Endure?

Perhaps more importantly, Philonise Floyd, the younger brother of George Floyd, who told me he’s hardly slept more than two to three hours a night since the trial began, was there to see it in the courtroom. An unassuming man thrust into a central role when George, the family’s sun, was killed, Philonise Floyd likes a flashy suit but speaks softly and slowly. He came to the hotel and told his wife, his brothers and cousins, a nephew and a niece—plus a smattering of activists, civil rights icons and those who wish to be—what he witnessed. The justice system had affirmed that what happened to George Floyd was wrong. It was unnecessary. It was murder. Then, in bits and pieces, in scattered conversations around the ballroom, the family began to talk of what they must now do for others like them.

And there will be others. Even on that day, the list of Black people killed by police grew longer. To Black people inside and outside that Minneapolis ballroom, a conviction in the death of one Black man is unlikely to tip the scales, to make anyone feel that police accountability and equal justice can now be counted upon.

I thought of the day I turned 16. My father took the morning off to deliver me to my driving test. When the driving evaluator and I returned, I walked through the door and flashed a thumbs up. My father, sincerely one of the best cheerleaders of daughters to ever live, stood and applauded. At least four or five people around him joined in. He had, of course, told them what I had come for and roped them in with his enthusiasm. My father insisted on a picture of me, my paperwork and the evaluator, as well as one with the woman who issued my first license.

When we left the building, he handed me the keys to his car and told me I would drive us to a celebratory lunch. But before I could put the key in the ignition, my father put his hand on the wheel and said, first we must talk. That was the day my father told me what I must do if stopped by the police, in hopes that I would come home alive. It was advice gleaned from cases he had seen, cases he had handled and grieving families he’d advised. Sharing it, my father, a lawyer who until that day I thought feared no one and nothing, said this advice was no guarantee. We are descended from people who survived the Middle Passage, arrived in chains, made this country so rich that slave patrol forces were built to keep enslaved and later free Black people inside racial boundaries. And now, was it any wonder, he said, there were people entirely uncomfortable with what it means for us to be free? This conversation is all that Daddy can offer you, Janell, he said. Take it seriously.

When you are Black and interact with a police officer—or a private citizen who wants to be one—the possibility that anything and nothing at all can get you killed is always there. And if you are Black and the police were involved, it is unlikely their claims will be properly investigated and any misconduct pursued to the full extent of the law. And yes, there is something particularly grotesque about unrequited injustice crashing in on your life when it is the handiwork of the justice system itself.

We came so close to George Floyd’s killing falling into that gap. His death was initially described by the department as “a medical incident.” Chauvin’s superior testified during his trial that Chauvin did not immediately report that when Floyd left the scene in an ambulance he was already dead. Private citizens, most of whom were Black or Latino, reported Chauvin’s conduct at least 18 times, with some mentioning that what they considered his excessive use of force had centered on their necks. And yet Chauvin—who, under Minnesota law, had the discretion to write a summons for the counterfeit 20-dollar bill that Floyd was accused of spending, rather than making an arrest —was training others on the job.

Last spring, in the early days after Floyd’s death, I went to Minnesota in the middle of a pandemic, with my asthmatic lungs, because I knew that something significant was taking shape if people in Minneapolis were willing to stand up, to keep yelling, to keep marching, even to burn things down, because a police officer had suffocated a Black man to death under his knee. While the death itself was brutal, death by police use of force is unfortunately common—for men of color, but particularly Black men. (Police use of force, something one of Chauvin’s expert witnesses tried to tell jurors they were not seeing in the video, is, one 2019 study found, the sixth most common cause of death for young Black men.) This time the response felt different. By the time I arrived, the National Guard had been called out. Men in fatigues with long guns were visible on the city’s streets. Food and water were hard to find. But no one who wanted answers seemed deterred. As far as I can tell, they still aren’t today.

In the months that followed, the sense that this time was different remained. And now, with the word guilty uttered three times, it is. Now, the members of the Floyd family to whom I spoke told me they will return to their homes, but not to their lives as they once were. There will be work to complete, children to school, meals to make—but also healing to do, and the looming possibility of trial for the three remaining officers, whom some expect will attempt to strike plea bargains. There’s the question of what becomes of the memory of Floyd, an ordinary man in life whose face and name now dot the landscape. For those who loved him, there’s been some justice, still George, Big George, Perry, Floyd is gone.

Then, there are the tasks that remain for the rest of us. The aversion to taking police and their press releases at their word; the effort to interrogate an officers’ actions when someone dies, just the way anyone else’s would be; the capacity to humanize Black victims of police violence, and to swiftly knock down stereotypes that have for so long passed as evidence—these things need to become the norm in courtrooms, in prosecutors’ offices, in newsrooms and in elected offices. Activists, grieving families and their lawyers have already done a lot to get us where we are. Rather than let the wordless sounds of this moment fade in our ears, their voices must remain.

0 Comments